The Half-Way Covenant

Our early New England Congregational forebears became members of the church by experiencing a conversion. Their children were baptized as infants, just as we do now. When these children grew up they of course wanted full church membership and to partake of the Lord’s Supper. But, in order to be granted that membership and communion they were expected to give evidence that they, too, had experienced a conversion.

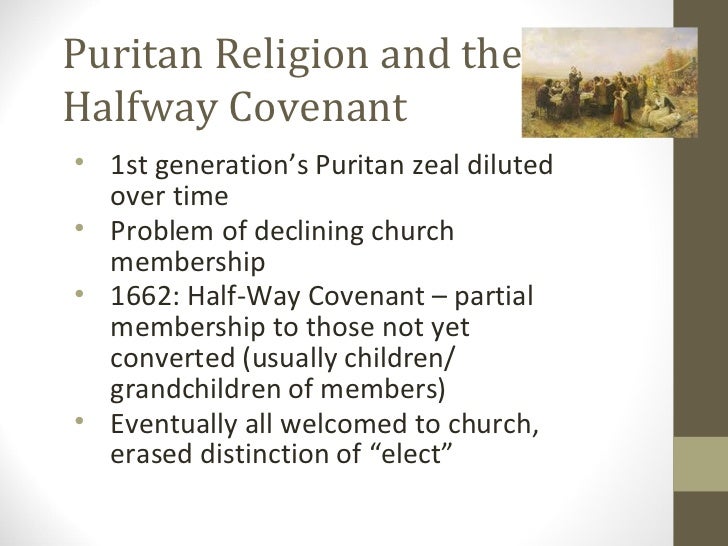

Many couldn’t report such a conversion and were therefore considered quasi-members: permitted to be baptized only because they had had parents who had experienced a conversion. The membership was partial; they did not partake of the Lord’s Supper, could not vote, and could not hold office.

New England had been founded and was operated on the very tenets of the faith as purified and refined by the church reformers of the British Isles and Europe. Local governments here were founded and conducted out of the churches, their laws drawn up in accordance with scripture, their magistrates and all officials full converted members of the churches, and taxes levied on all citizens paid for the churches. This was long before the U.S. Constitution was written.

The children of the children of the original members created a whole new problem for the New England church. Could they even be baptized? They were children of “unconverted” church members, after all. Controversy swirled.

Church membership would decline by attrition in one generation unless an answer to this dilemma could be found. The original members had been converted first-hand. The next generation had been raised by the converted but had not experienced it themselves. The third generation had been raised by baptized but unconverted parents. What to do?

A solution was found. The Half-Way Covenant, as it was later called, to accept children for baptism and church membership. This had the effect of increasing the roles as well as encouraging conversion and working to benefit the church. The idea was acceptable to the majority of New England churches until the 18th century, when the “Great Awakening” taught that church membership was only valid through genuine faith conviction.